Your cart is currently empty!

Roseville Railyard Explosions

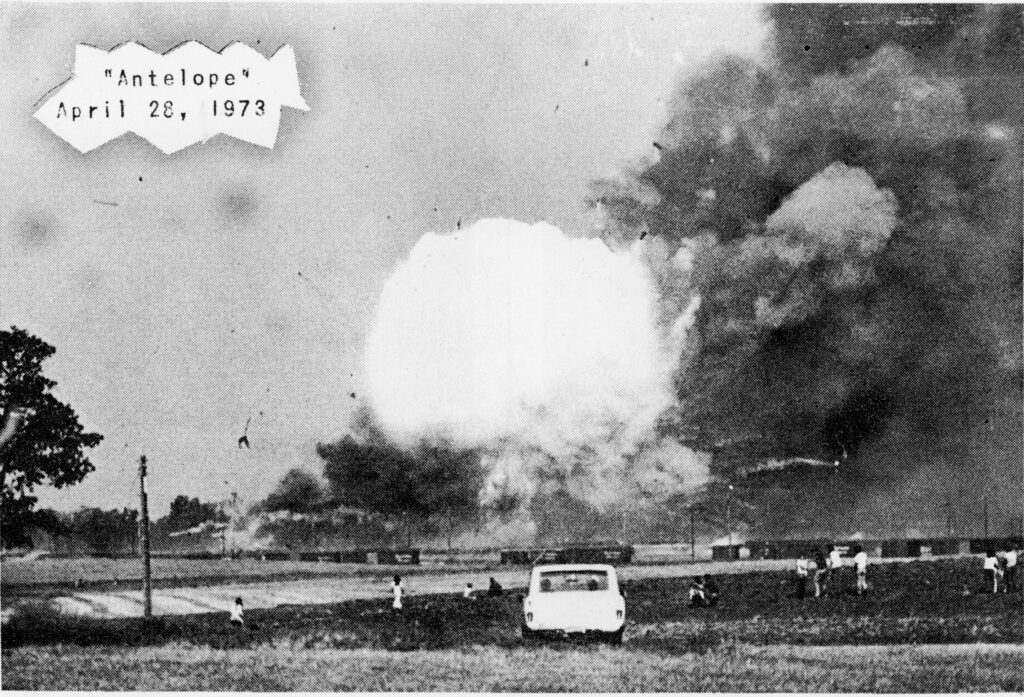

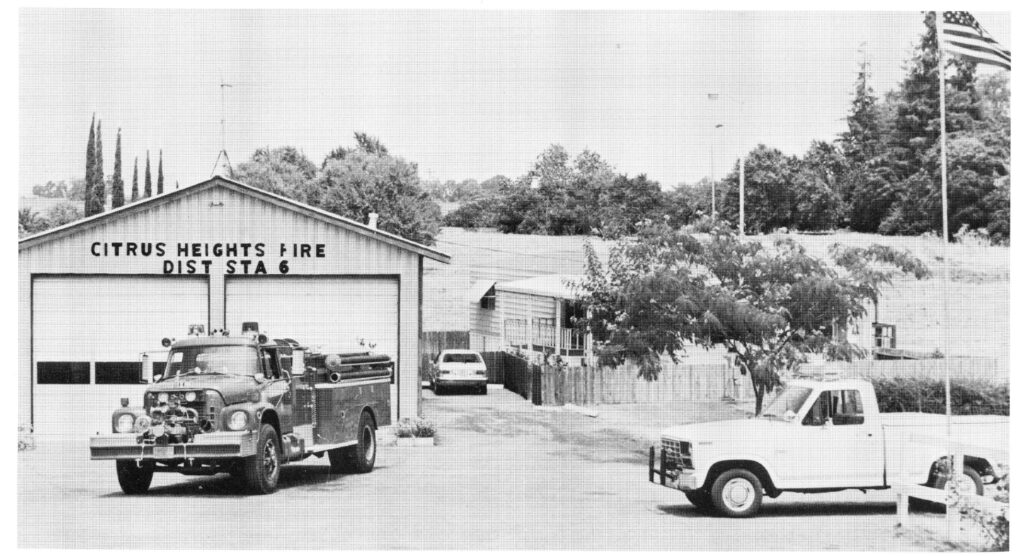

Citrus Heights Fire Battalion Chief, Lloyd Patterson, arrived at Fire Station 6 on the morning of Saturday, April 28, 1973. Located in the town of Antelope, the tiny fire station had just been completed the day before and Chief Patterson was there to inspect it. Lt. F. Grundy, who lived at the station along with his wife who was about 9 months pregnant, were there also.

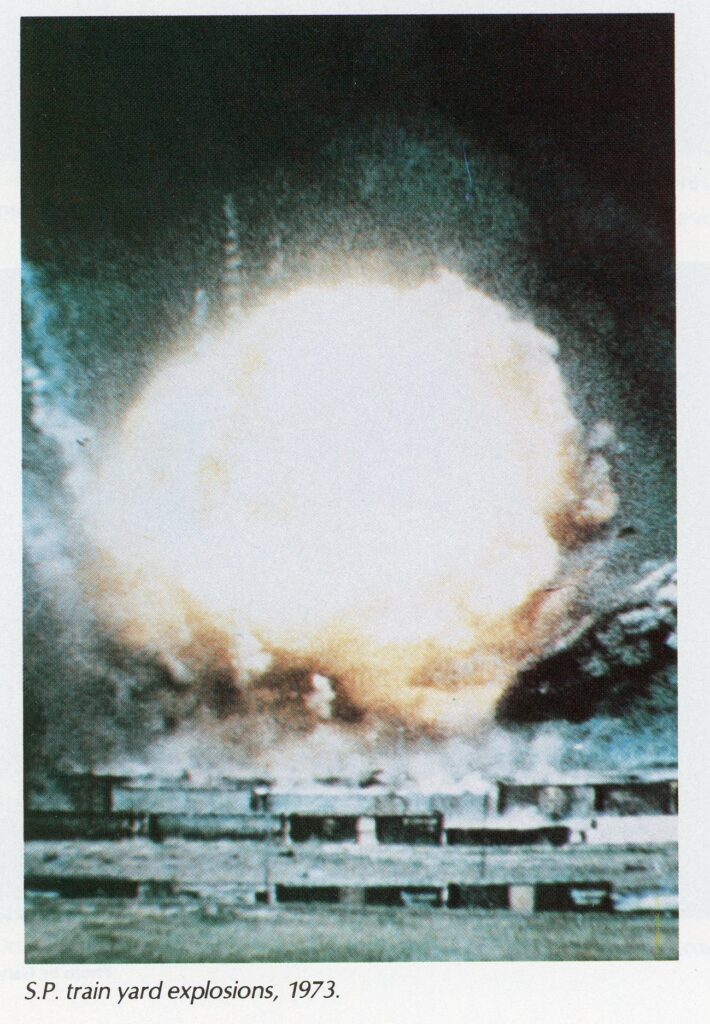

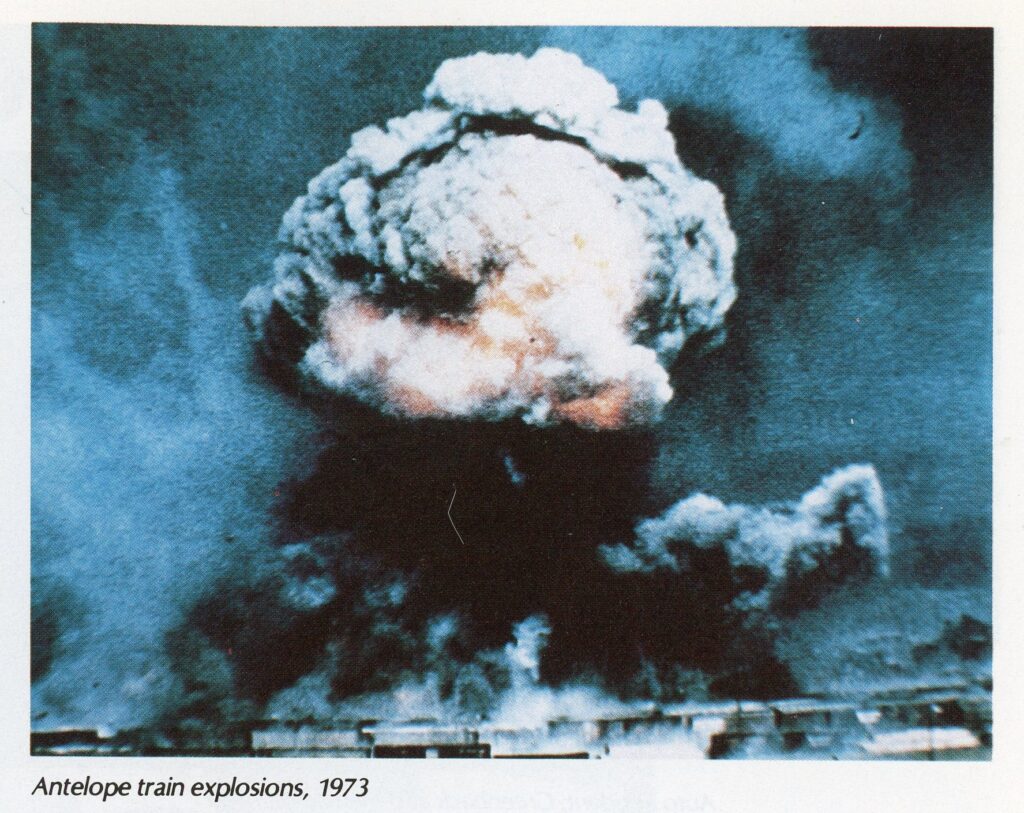

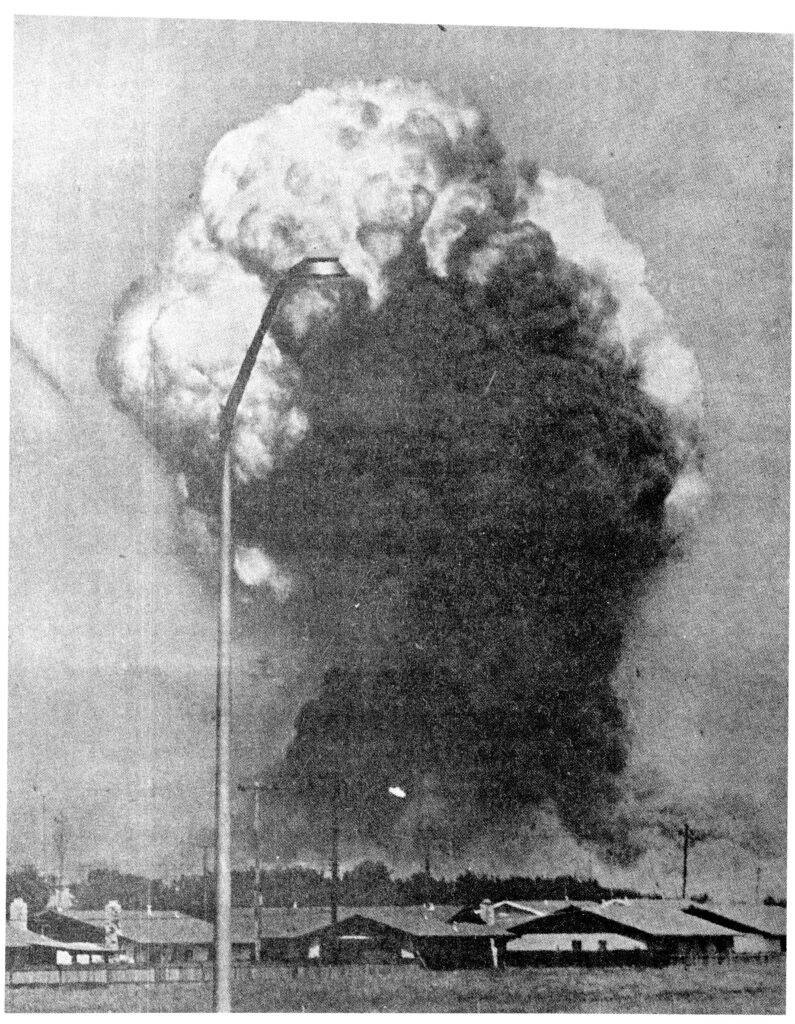

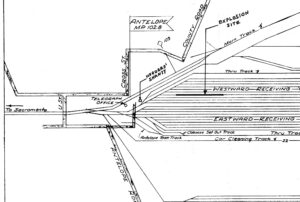

While inspecting the station, Patterson and Grundy noticed smoke and a small explosion coming from boxcars in the Roseville Railyard just a couple of hundred yards away. Patterson called the dispatcher to send equipment, then went into the railyard to assess the situation. On his way in, Patterson met two Southern Pacific employees who had also witnessed the smoke and explosion. While Patterson and the employees exchanged information, the first high order explosion occurred at 8:03am. It knocked them all flat on the ground.

Chief Patterson immediately went back to the fire station and evacuated Lt. Grundy and his wife. As he did, 250-pound bombs that were loaded onto 18 Department of Defense boxcars destined for Vietnam began to explode, sending fireball after fireball into the air that could be seen for miles. In about two hours, the 18 boxcars were obliterated. Many of the 1,200 bombs inside of the cars though were thrown out onto nearby fields. The fields caught fire detonating the bombs. These explosions lasted until 4:00pm the following day.

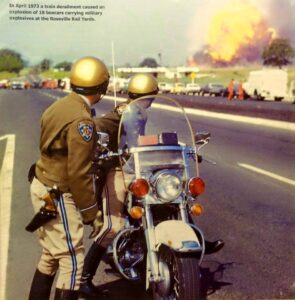

Nine emergency service agencies – local, state and federal – responded to the explosions. About 30,000 people were evacuated from the nearby towns of Antelope, Roseville and Citrus Heights. The National Guard maintained a heavy presence within a two-mile radius of the explosions, which extended to Sylvan Corners. To many residents, Citrus Heights felt like a war zone.

Everyone who lived in Citrus Heights at that time can remember where they were when the bombs went off. Many of those who lived on a hill watched from their homes. Others found viewing vantage points on nearby freeway overcrossings. Some managed to get past barricades and got up close. The Citrus Heights FD described this last group of people as having “curiosity that exceeded their intelligence”. Movie goers at the Sunrise Drive-In Theater at Greenback and Fair Oaks on Saturday night said they could see the orange flash of bombs to the right of the movie screen. Some said the bombs were more interesting than the movie.

Miraculously, there were no fatalities. About 350 people were injured. Most of these were minor injuries from broken glass. 5,500 structures were damaged, mostly residential. Southern Pacific paid out 23 million dollars (in 1973 dollars) for the damages. Of the 32 buildings in the town of Antelope that was closest to the blasts, 12 were slightly damaged, 11 received heavy damage and 9 were completely destroyed, including Citrus Heights Fire Station 6.

A Department of Transportation report determined the most probable cause of the explosions was a “hotbox”, or overheated wheels, on one of the boxcars. Eyewitness reports stated that a wheel on one car was glowing red as the train came down the Sierra Nevada Mountains. It was thought that this wheel may have caught the wooden floor of the boxcar on fire, which in turn ignited the bombs. An unstable bomb, however, could not be ruled out as a cause because the evidence had been destroyed by the explosions.

Please click on any of the thumbnails below to enlarge.